If you’ve ever experienced the anxiety of an upcoming review, or the knot in your stomach when your manager asks for a quick word, you’re not alone. Getting feedback in any form is stressful: it makes us feel vulnerable and often defensive; so often, we feel as though the other person isn’t criticizing our work, but who we are as people. However, it’s also the key for growth and learning; without it, a person can end up stuck, or even fall into a bad habit without ever knowing. It’s necessary, then, to learn how to take feedback well.

Hopefully, your workplace is full of people who know how to give constructive feedback in a sensitive manner; either way, though, it’s important to learn how to take feedback and make it work for you, rather than be brought down by it. According to Sheila Heen and Douglas Stone, the gurus behind Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well, “The skills needed to receive feedback well are distinct and learnable. They include being able to identify and manage the emotions triggered by the feedback and extract value from criticism even when it’s poorly delivered.” Thankfully, there are strategies we can use to get better at receiving feedback, the next time it happens.

1. Disconnect feelings and take a step back

2. Ask ‘clear and curious’ questions

3. Evaluate feedback

4. Asking for feedback

Disconnect feelings and take a step back

At the end of the day, we all just want to be accepted as ourselves— which is why feedback can feel like a personal attack. According to Heen and Stone, though, “Getting better at receiving feedback starts with understanding and managing those feelings.” Recognize that feedback can feel threatening, understand that those feelings are natural, then set those feelings aside and review the feedback objectively.

Often in employee feedback examples, the person receiving feedback tends to pick apart the feedback they’ve received, looking for the ways in which it’s wrong. However, it can be far more beneficial to take some time to decide how you feel about the feedback, and whether any of it is correct.

Additionally, Heen and Debbie Goldstein note, it can be really beneficial to recognize that what we interpret feedback as, and what the giver is trying to say can be two completely different things. So, writing off the feedback someone gives you can mean, “...you’ll dismiss it too quickly — before you actually understand what the feedback giver is trying to tell you.” Instead, take a step back, cool off, and try to determine whether there’s a kernel of truth to the feedback— or whether you’re misinterpreting something.

Example: One day, your boss asks you to come to their office after lunch for a quick touch base. Once you’re there, they tell you that they think you’re doing a great job, but that they want you to be more generous. Your knee-jerk response to this negative feedback, internally, is outrage; you’re extremely generous— you regularly bring in homemade treats to share, and you’re a supportive team member. However, instead of dismissing your boss’s feedback, you take a deep breath and try to distance yourself from those feelings.

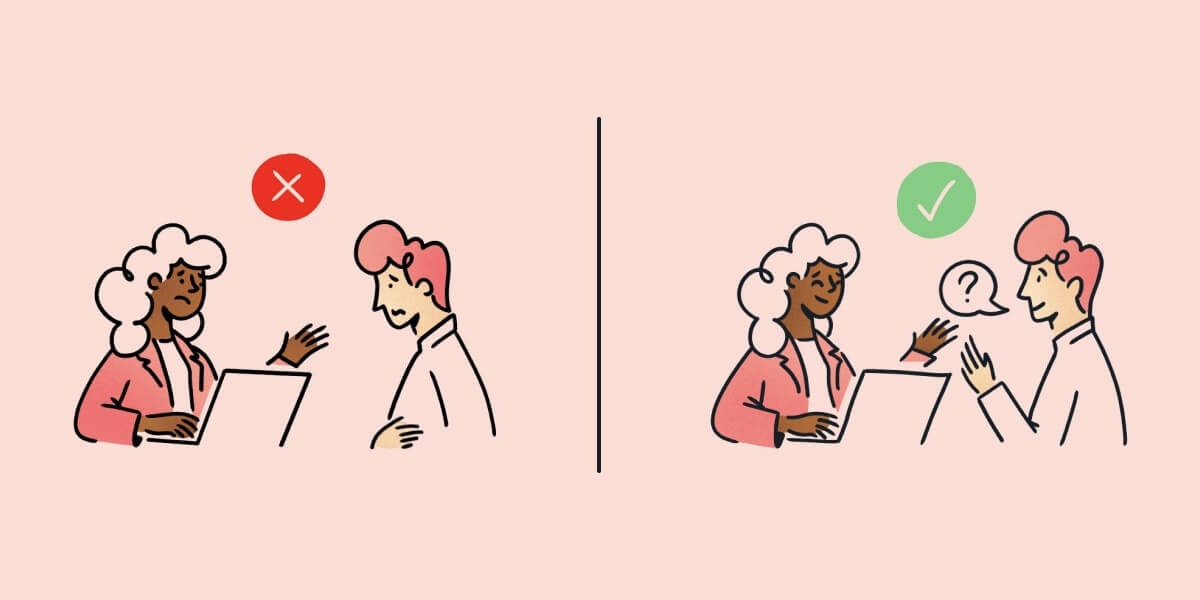

Ask ‘clear and curious’ questions

Heen and Goldstein advise never taking for granted that you fully understand the feedback you receive. You may interpret certain words differently than the feedback giver, or they may give feedback referring to a specific aspect of your role without explicitly saying that— which can impact how valid you find their advice. On that note, it’s also important to realize that the person giving you feedback might not be very good at doing it. In an ideal world, everyone would know how to give effective feedback in a way that the recipient felt comfortable in getting it. But giving feedback is as hard a skill to learn as receiving it, and it’s important to realize that when receiving feedback, because it’s more important to focus on the content of the feedback than the method by which it’s provided. After all, as Stone shared in an interview with Forbes,“We can’t let our own success, education, and advancement ride on whether the person giving us feedback happens to be talented or caring.”

To counteract this, Sheen and Goldstein advise to “always assume givers will need help articulating what they mean. And that the way to help them — and yourself — is by asking clear and curious questions without a defensive tone.” Sometimes your feelings or point of view can cloud your judgment and understanding of the focus of the feedback. Operate from an open attitude and ask genuinely curious questions like:

- Can you say more about what you mean when you say [x]?

- Can you be more specific about what [x] means to you, and what your expectations are?

- Can you give specific examples of times when I was / wasn’t [x]?

- What does [x] look like to you?

- Can you give examples or suggestions of what you think I can do differently to be more [x]?

These questions will help you get to the root of what the feedback really is, and then you can evaluate its validity, and what you want to do about it, from there.

Example: You decide to ask your boss more about what they mean when they say generosity, and in what areas they think you could exhibit that quality more. It turns out that they think you could be more generous in interfacing with and supporting other teams and their members; your role in your own team doesn’t even factor into this feedback.

Evaluate feedback

If you’ve asked questions and your feedback examples still don’t feel right, ask a trusted peer if they’ve noticed the particular habit/ behavior/ etc. about which you’ve been given feedback. You can ask:

- Is there anything about that feedback that might be right?

- Is there anything I do that could be interpreted as [x]?

You can also experiment: if the risk is low, but the potential positive outcome if you follow up on some feedback is high, it might not hurt to test it out. However, you always have the option of not acting on it, as well. Being good at receiving feedback means hearing and trying to understand it, reflecting, and looking for the part of it— even the small part— that’s of value. Then, you decide on whether to act on it. If you don’t, you should touch base with the feedback giver and share your thinking— that way, they will know you heard and took their input seriously, rather than that you are ignoring it.

Example: Now that you think about it, there are a couple instances where you could have been more generous— you said you’d “have to see if you had time” to walk a coworker who’s trying to grow into management through what your team is responsible for, and when another department asked you to give them some data before last month’s meeting, you did sigh and mention that it was a really inconvenient time. Those are definitely instances where the critical feedback is pretty appropriate.

Asking for feedback

Heen and Stone note that if you ask for feedback regularly and directly, you are less likely to have the experience of it being confusing or upsetting. Additionally, “Research has shown that those who explicitly seek critical feedback (that is, who are not just fishing for praise) tend to get higher performance ratings.” However, you don’t want to ask an unfocused question like, “Do you have any feedback for me?” Instead, ask something like:

- What is one thing you see me do (or not do) that keeps me from accessing my potential?

- What would you say my greatest strength is as a coworker, and how do you think I can amplify that?

Example: You make a conscious effort to show up when other teams need you, and even offer help proactively; you also begin to ask for feedback more regularly to make sure you’re growing in the right way.

Learning to take feedback well takes some work: you have to figure out how to manage your feelings; how to ask questions to ensure you understand the other person’s suggestions; and how to then evaluate whether you want to enact changes. However, developing the skill of receiving feedback well— and even proactively asking for it— can vastly improve your work relationships and impact your growth, so it’s worth putting in the time and effort.